Rene Magritte: “Toute en Papier” at Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Aristide Maillol, Paris — March 8 – June 19, 2006 / reviewed by Nava Atlas.

Rene Magritte: “Toute en Papier” at Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Aristide Maillol, Paris — March 8 – June 19, 2006 / reviewed by Nava Atlas.

“My painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself the simple question, ‘What does that mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, either, it is unknowable.”

Many images created by Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte (1898-1967) are iconic, even to those without a great deal of background in modern art: The bowler-hatted man with an apple floating before his face; a locomotive zooming out from a fireplace; a giant comb leaning on cloud-painted walls. Magritte, with the quote above, frees viewers from struggling to understand his work. He invites them, instead, to share a sense of wonder at how such images float to the surface, often unbidden, tapping into a portion of the consciousness that is uninhibited, curious, and often simply playful.

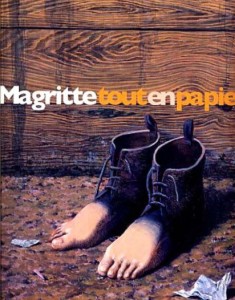

In this exhibit, the image that first greets the viewer is a gouache of a pair of boots whose leather segues into toes made of human flesh. This gouache study hints that the rational mind should be left at the door, and the viewer steps into the mind of a classic surrealist. “Tout en Papier” is a comprehensive exhibit of Magritte’s small works on paper created from the 1930s through the 1960s, near the time of his death. They cover a wide range of media and styes, from sketchy notebook pages to tightly rendered gouache studies.

Founded by André Breton in 1924, the surrealist movement aimed to tap into the unconscious mind, creating a reality truer than what is manifest, more real than real, thus surreal. Magritte belonged to a core group of surrealists who had broken from the Dada movement, which included Breton, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy, Joan Miro, and Meret Oppenheim, among others. Salvadore Dali was also at the forefront of this movement, but was later marginalized sue to his right-wing views. Magritte was apparently not one of the more outspoken leaders of the charge, preferring instead to focus on creating his prodigious body of work.

Exhibits of surrealist works can often be gaudy and gimmicky, emphasizing the shock and titillation such images provoked when surrealism was new. However, with these small works, Magritte pulls the viewer in close for a rare look at the process and development behind some of his best-known works, Yet, the images from some of his most famed works, including some of those mentioned above, are conspicuously absent — hinting that certain subjects were held closer to the artist’s heart. The works on paper evoke intimacy, and quite often delicacy. Whether done in pencil, ink, gouache, collage, or a combination, show a mastery of each medium.

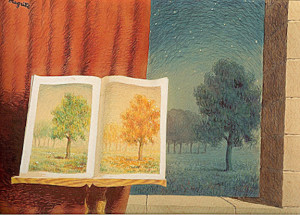

The surrealists developed a long list of techniques for working on paper and canvas, including frottage, fumage, grattage, and collage. Collage seemed to have found most favor with Magritte. In one of the many such works from the 1930s, he combines various media with collaged textures. Sheet music predominates, becoming the background for curtains, doors, and instruments. He often revisits favored images decades later; in this case, he does so with Le Savoir (1961); a door and its frame, resting in the middle of a room are made of sheet music opened onto a night sky; above them, outsized parts of two violins float, also made of sheet music.

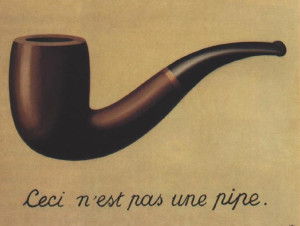

One of Magritte’s best-known images, the pipe declaring that it is not a pipe (Ceci N’est Pas un Pipe) held continuous fascination for the artist. Over the years, he rendered the image in a number of media. Titled Le Trahison des Images (“The Treachery of Images”), this was originally a statement on representation and realism done in 1928. Of course, this is not a pipe, but an image of a pipe. In La Liberté des Cultes (1946), the pipe floats hugely in an oil-painted sky recalling Van Gogh, minus text. Another version of the pipe appears again in 1966, titled Les Deux Mysters, drawn simply in ink. Magrite was no doubt fascinated by the dissonance between reality and its representation by image as well as language; the mystery here, perhaps, is why a pipe, and why did this particular image, or symbol, hold an almost lifelong fascination for him?

One of Magritte’s best-known images, the pipe declaring that it is not a pipe (Ceci N’est Pas un Pipe) held continuous fascination for the artist. Over the years, he rendered the image in a number of media. Titled Le Trahison des Images (“The Treachery of Images”), this was originally a statement on representation and realism done in 1928. Of course, this is not a pipe, but an image of a pipe. In La Liberté des Cultes (1946), the pipe floats hugely in an oil-painted sky recalling Van Gogh, minus text. Another version of the pipe appears again in 1966, titled Les Deux Mysters, drawn simply in ink. Magrite was no doubt fascinated by the dissonance between reality and its representation by image as well as language; the mystery here, perhaps, is why a pipe, and why did this particular image, or symbol, hold an almost lifelong fascination for him?

Gouache was a medium that Magritte exercised with ease and grace. Sometimes, it was used almost as a way to draw, with rough, loose lines, and in other works, to render precise studies of pieces that would become large oil paintings. Many of the gouache studies are small, no larger than 9 by 12 inches, richly detailed and colored but somehow gentler than the large oil painted versions. Margritte used gouache to render several versions of Scheherazade, for example, so exquisitely that these little studies are almost jewel-like.

At times, Magritte returns to major works decades later by revisiting them with gouache studies. He revisits the man in the bowler hat (sans apple) in the 1960s, at the end of his working life, for example, in a series of gouache studies. Like the pipe, the bowler-hatted man seed a kind of touchstone of Magritte’s vision.

In contrast to the work of many surrealists, which often presents the viewer with disturbing, almost nightmarish images, Magritte’s works on paper mainly depicted everyday objects. Curtains, birds, clouds, leaves, doorways, trees, hats, and shoes are all fodder for his dreamlike minds capes. The image that might be weirdest in this context is the woman’s face whose features are actually a female nude body. Indeed, given the subtle and gentle nature of most of the pieces in this show, this one stands out as particularly bizarre.

In contrast to the work of many surrealists, which often presents the viewer with disturbing, almost nightmarish images, Magritte’s works on paper mainly depicted everyday objects. Curtains, birds, clouds, leaves, doorways, trees, hats, and shoes are all fodder for his dreamlike minds capes. The image that might be weirdest in this context is the woman’s face whose features are actually a female nude body. Indeed, given the subtle and gentle nature of most of the pieces in this show, this one stands out as particularly bizarre.

Though Freudian theory played a role in the development of surrealism, Magritte objected to the use of psychoanalysis and symbology to understand his art. In its time, Magritte’s work was (despite its ostensible simplicity) considered difficult. He wished for his work to liberate the viewer from pedestrian vision and into a realm where even the mundane can astonish. he aimed to conjure a new way of seeing, feeling, and thinking — without overthinking. For the modern viewer, much more inured to graphic and disturbing images than were viewers of the work ehn it was new, this comprehensive exhibit is likely to delight far more than it might chagrin or upset.

Rounding out the exhibit is a display of limited edition books to which Magritte contributed, whether cover designs or writings. As well as correspondence dense with writing and little sketches, delving in depth into his though presses and opinions. One would need to be fluent in French to appreciate these letters fully, though they are quite lovely to look at.

Even absent his meticulously rendered oil painting, this exhibit portrayed Magritte as a master technician. But more than that, it allowed a rare glimpse at the artistic process that ran parallel to creating numerous iconic images. Magritte emerges as both a rigorous thinker and a wit. An exhibit that displays such breadth as well as depth is a testament to the enduring legacy of surrealism in general, and Magritte’s influence in particular.